By late evening of August 21, 1991, the Neo-Stalinist Putsch in Moscow was falling apart. I was a 25 year-old American-Lithuanian, and I’d been living in Lithuania since January 1991. I arrived on January 15, 1991, two days after Soviet tanks and soldiers occupied the Lithuanian TV tower and media centers, killing 14 and injuring over 700 unarmed civilians who protected the buildings as human shields.

During these months I’d witnessed the crazy slow collapse of the Soviet Empire while Lithuania tried to break free from the USSR. Working inside the barricaded Lithuanian Parliament in Vilnius, in the InfoBureau (Press Office) as an editor and spokesperson, I’d experienced every emotion possible, however, I was not prepared psychologically for what occurred in Vilnius in the final hours of the Moscow Coup.

I arrived for work at the Lithuanian Parliament building on August 19th and hadn’t left my post manning the phones at the InfoBureau for over sixty hours straight. Soviet President Gorbachev had been removed from power and taken hostage in the Crimea by a group of Neo-Stalinists who wanted to turn back time and shut the Iron Curtain around Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia once and for all.

I received calls from foreign diplomats and journalists throughout the USSR attempting to get information of what was occurring in Lithuania. The InfoBureau had also become a hotline for Lithuanian citizens to report Soviet military aggression. The phones were ringing off the hook with reports of columns of Soviet tanks and seizures of buildings.

During the three days of the Putsch, while all eyes were on Moscow, Soviet troops were active throughout Lithuania preparing to overthrow the Lithuanian government, led by Parliament Chairman, Vytautas Landsbergis. We were barricaded inside the Parliament building, preparing to be attacked. Even after the deaths and injuries in January during the Soviet military seizures of building, unarmed civilians to gather again to serve as human shields.

(Actual video footage from Aug. 19, 1991 of citizens serving as human shields at the Lithuanian Parliament building: https://youtu.be/cQXTAdeoty8?list=PLCB7E93D1F9C3CF37 )

Citizens at the Lithuanian Parliament building serving as human shields during the August 19-21, 1991 coup

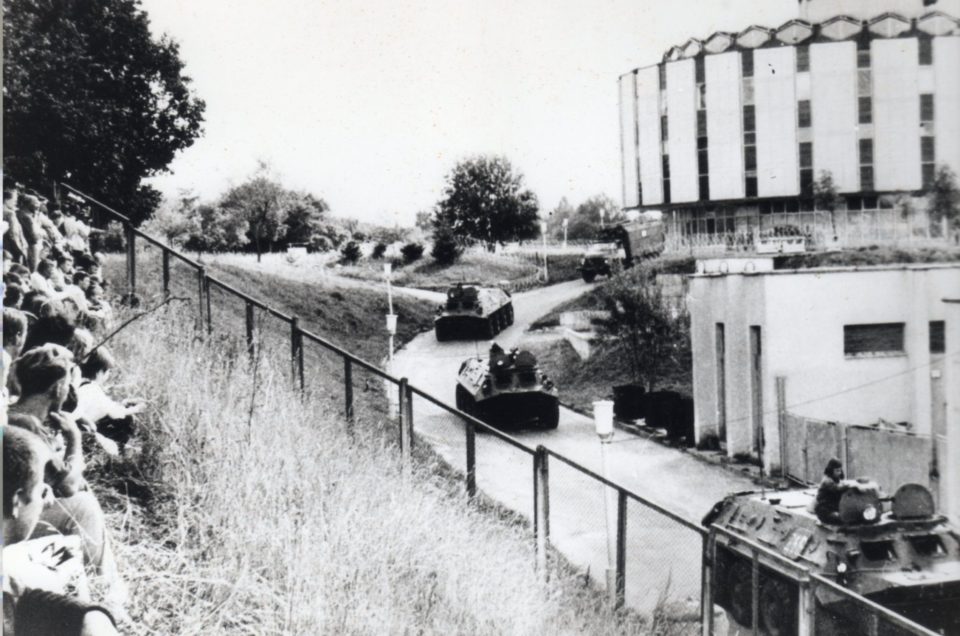

Soviet troops quickly seized dozens of buildings and transmission towers throughout the country since the early hours of August 19th. Checkpoints and armed patrols harassed citizens. In the evening of August 19th, one hundred Soviet tanks moved across Vilnius toward the Parliament building but were stopped by barricades at the foot of the bridge that crosses the Neris River.

The dozens of tanks positioned themselves to face the Parliament building.

Citizens scrambled over the barricades and stood in front of the Soviet tanks, shaking their fists.

Inside of the Parliament building volunteer guards ran through the offices yelling at us to get on the ground and shut out the lights. My co-worker and I were frozen in fear staring out the window at the tanks.

The tank barrels jolted back and forth, taking aim.

We waited for the tanks to shoot. I could feel the reverberation of the tanks’ engines traveling across the bridge through the foundations of the Parliament building to the soles of my feet.

“I don’t want to die,” played like a mantra inside my head.

The Soviet soldiers waited for Lithuanians to shoot first.

Lithuanians waited for the Soviet soldiers to act first.

(Video footage of Soviet tanks and military on the outskirts of Vilnius on August 19, 1991, preparing to attack the Lithuanian Parliament building: https://youtu.be/Q00QJVeIBko?list=PLCB7E93D1F9C3CF37 )

Daiva stands on the barricades that prevented Soviet tanks to approach on August 19, 1991. Parliament is in the background

A half hour standoff occurred.

Citizens restrained themselves and didn’t provoke the Soviet soldiers. They didn’t throw rocks or show any other aggression toward the soldiers, which could’ve been used a pretext for the tanks to start firing.

No shots were fired.

After a half hour, the tanks withdrew.

But the danger was not over. Every few hours a new threat appeared while my co-workers and I tried to get information out to the world, since we believed this might be our last chance to tell the world what was happening in Vilnius.

At one point, our InfoBureau fax operator, Arvydas, called me into the fax room, “I want to show you something on the telex machine.”

Arvydas Repšys – InfoBureau telex/fax operator manager

I stood over him while he continued, “I programmed shortcut messages just in case things get crazy—in case I can’t get messages out. We also might not have time before our power gets shut off to send any last minute messages. I made things simple. You remember how to work this thing?”

Daiva types a press release onto the telex machine

It was a Russian telex machine, with a Russian keyboard, but he taught me how to send out press releases months ago. I replied, “Yeah, hit the pre-programmed message number. Then the send keys like you showed me and it goes out to all our telex numbers at once.”

The numbers included foreign news agencies, foreign diplomatic offices and governments.

“Right,” he continued, “Now, message #1 is ‘We are surrounded.’”

I don’t like where he is going with this, I thought.

“Message #2 is ‘We are under attack.’”

I bit my lip.

“Message #3 is ‘We are dead.’”

I realized, when the bullets started coming at us, Arvydas planned to stay at the telex machine and hit message #3 himself before he dropped dead. And he expected me to send out the message if he was killed before doing so. There was no time to think about such morbid possible outcomes.

“Okay, I understand” I said, “I can handle it if I have to.”

When I turned to leave, a Lithuanian volunteer guard appeared in the fax room doorway blocking me and addressed Arvydas, “Do you want a weapon? A pistol?”

“Uh, no. I’ll be all right,” he said shocked.

A Lithuanian volunteer guard inside the the Vilnius Parliament building during the August 19-21 coup.

The guard disappeared before I could tell him I’d like a gun. Women were told to leave the building, but many of us remained. I thought it was rather sexist I wasn’t offered a gun, not that it would be much help against tanks.

On the third day of the coup, when Soviet military helicopters flew over the building, we thought paratroopers were going to drop down on the roof.

Thoughts of how I might be killed circled in my mind. My nerves were shot. Some time during the blur of the three days I, along with a group of co-workers and volunteer guards, received last rites from a Catholic priest. Even Landsbergis told me in the middle of one night when I delivered a fax to him, in a fatherly way, “May God be with you.”

It didn’t look good for any of us.

However, by late evening on August 21st, it was clear the Moscow Coup was failing, even though we didn’t have much information. We received most of our information from the calls that came in, from journalists and others like us, opposing the Coup, barricaded inside of their government buildings. The rumor was that the Coup leaders were on the run, attempting to escape by plane. There was confusing information about the Soviet military withdrawing, but we still had reports of them seizing structures. Along with my co-workers, including my boss, Rita Dapkus, I’d been awake for about three days straight (powered by Nescafe and cigarettes and anxiety). I didn’t want to be napping when the Soviets attacked us and killed me, so I just stayed awake.

At 10:45 p.m. on Aug 21, I was doing my job, staring out the fourth floor window speaking on the phone with two journalists at once, one from the London Times and the other from Reuters. The phones were ringing off the hook, and I had to be efficient in providing the updates.

Unarmed citizens continued guarding the building, just in case the Coup was not officially over. There were about 5000 people outside.

Citizens at the Lithuanian Parliament building serving as human shields during the August 19-21, 1991 coup

The TV Tower, occupied since January 13th, loomed on the horizon—a faint light emanated from its offices on the lower floors.

While I spoke simultaneously into both phone handsets, several flashes of light and explosions suddenly erupted outside. Gunfire rattled the windows.

We’re under attack! I screamed in my head.

My mind tried to understand what I was seeing.

Light continued to flash to my right—at our street entrance checkpoint.

A Soviet military Jeep zoomed past the checkpoint alongside of the river in front of the Parliament building, right past my window.

People outside ran toward it.

Multiple flares shot into the sky, which reflected in the river below.

The Jeep made a u-turn and headed back toward the checkpoint.

More gunfire.

Two flashes of light.

People running everywhere.

An ambulance whizzed past toward the checkpoint.

“What was that!” the journalists yelled over the handset.

“Gunfire!” I said, “I think a Soviet miltary jeep broke through our checkpoint! I gotta go! Call me back in twenty minutes.”

Arvydas was ahead of me when I ran out of the office. I followed him through the maze of obstacles, sandbags, Molotov Cocktails and past volunteer guards mobilizing for an attack.

Barricades inside of the Lithuanian Parliament building during the August 19-21, 1991 coup.

I didn’t know why our instant impulse was to run toward the gunfire.

We weren’t the only ones.

A large crowd surrounded the action. The gunfire and explosions had just ended. The air smelled like fireworks. Our volunteer guards had quartered off the area and were keeping people back. Citizens shouted and yelled. The scene was chaotic. Several Parliamentarians were already outside and motioned the guards to allow Arvydas and me through.

A few feet away, a young man dressed in green fatigues screamed in pain when he was lifted onto the ambulance stretcher. His backside was covered in blood. He turned to us and screamed while he was gently placed face down on the stretcher.

He looked confused and shocked this was happening to him. His bright eyes met mine as he released a long, silent cry. I didn’t know if he was a Lithuanian volunteer guard or a Soviet soldier. It didn’t matter. My heart filled with compassion for him. None of us wanted this. How many more people needed to die? It didn’t have to be like this. I had to look away.

I asked the Parliamentarian what happened.

“An OMON jeep drove past the first checkpoint, threatening the volunteer guards with their weapons,” he said.

Lithuanian checkpoint on the approach to the Lithuanian Parliament building

While he spoke I noticed another injured young man in uniform placed in another ambulance.

“The Lithuanian guards tried to block the vehicle. But it broke through the checkpoint,” he continued.

I couldn’t help but look back at the first young man shouting in pain in the ambulance. He glanced back at me.

“The Lithuanian guards shot two flares. The jeep turned around and headed back toward the checkpoint.”

The doctors tried to hold the crying man down as they attempted to treat him.

“Gunfire was exchanged at this point. We don’t know who shot first.”

The bloodied young man finally calmed down.

A wave of nausea permeated my body. When will this end? I thought.

“One of our volunteer guards was shot and one of theirs was shot. Two OMON were arrested. One OMON escaped.”

After we gathered enough information, to ensure we’d be able to inform journalists calling in about what occurred accurately, Arvydas and I returned to the InfoBureau and informed our co-workers while we awaited further details.

Concerned citizens throughout Vilnius who heard the gunfire echo across the city or saw the flares called panicking, “Are you being attacked? Do we need to come to help defend the building?”

After everything that had occurred in Lithuania, from the tragic events of January 13th and the murders at Medininkai on July 31st, ordinary citizens were still willing to defend the Parliament building with nothing but their bodies. I spoke to many brave citizens that night assuring them it was over—after these never-ending months of threats, that they could finally sleep peacefully that night. Instead, outside the InfoBureau windows I saw more people arrive, setting up tents on the grass outside.

At three in the morning, a Lithuanian security official came up to the InfoBureau to provide us with an update on the information of the attempted provocation.

The Lithuanian guard who was shot was Arturas Sakalauskas. He was 27 years old. Only two years older than me. The Soviet soldier who was shot was a member of the KGB spetznaz special task force. He was armed with the same type of weapon that was used in the murders of the customs workers at the Medininkai post on July 31, 1991.

By then, we learned Gorbachev was on his way back to Moscow. We finally believed the Coup was over, and this tragic incident was a rogue group of KGB soldiers demonstrating a final show of power. We believed the Parliament was no longer under a threat of attack.

Rita gave me permission to take a nap. I collapsed onto the sofa in the hallway. Someone else was snorning away on another sofa. I pulled off my cowboy boots and was out before my head hit the cushions.

I woke up at 7:00 a.m., feeling relieved and revived with four hours of sleep.

After all these months, I wasn’t afraid of a pending attack or any more bloodshed in Lithuania.

After freshening up the best as I could, considering I was wearing the same clothes for four days, I cheerfully returned to the InfoBureau to check in with Rita.

“Don’t get too happy yet,” Rita said bringing me back to reality, “Landsbergis and defense chief Butkevicius have issued an ultimatum. If the Soviet military doesn’t withdraw from the buildings occupied since January, we’ll forcibly re-take them.”

The troops seemed to be withdrawing from the buildings they seized during the Putsch the last three days, but there were still twenty-nine Soviet military occupied buildings throughout Lithuania since January 1991.

Even though the Neo-Stalinist Coup d’Etat was over in Moscow—as long as the Vilnius TV Tower and other buildings in Lithuania were occupied by Soviet forces, a Coup d’Etat was still in effect in Lithuania.

Was Gorbachev finally ready to allow Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia to become free and independent nations?

Visions of Lithuanian volunteer guards battling tanks with old hunting rifles and sticks entered my mind.

“What do you mean by, ‘forcibly’?” I asked Rita to clarify.

Before she could answer, another co-worker interrupted us to inform us that, Arturas Sakalauskas, the young Lithuanian volunteer guard posted at the checkpoint had died.

Artūras Sakalauskas (1963-1991)

I wondered who I saw loaded onto the ambulances, was it Arturas or a KGB soldier? Part of me didn’t want to know.

With another death, the mood at the Parliament building was one of pending doom, again. Another young Lithuanian defender had given his life.

But this time, it was different.

We used to sit in uncertainty waiting to react to Soviet military actions. Now, Lithuanians were going to be taking matters into their own hands.

We weren’t waiting for the West or Yeltsin to help us.

Landsbergis called USSR General Moisejev and informed him if Soviet troops did not withdraw from the buildings that were seized by the Soviet military since January by 1:00 p.m. today, August 22, that Lithuanians, both citizens and volunteer forces, will take the buildings themselves. He left that open to interpretation.

I felt sick. I didn’t want anyone else to die. Not any more Lithuanians or Russians.

I could hear our volunteer guards running through the hallways of Parliament preparing for the consequences of our ultimatum.

[see next Blog post for the continuation of this story]

Next time you are in Vilnius and visiting the Lithuanian Parliament building, be sure to take a stroll behind the building along the street parallel to the river and parking lot. You will find a small memorial to 27 year-old Arturas Sakalauskas, the last Lithuanian victim of the five decade Soviet occupation.

Memorial to Artūras Sakalauskas, killed on August 21, 1991 while defending the Lithuanian Parliament building