In 1991 the TV Tower in Vilnius had become the symbol of the Lithuanian struggle for freedom.

After nearly five decades of the Soviet occupation, Lithuania re-established its independence from the USSR on March 11, 1990. But the Kremlin refused to accept the will of the Lithuanian people.

Why would the leaders of the USSR allow Lithuania to break away now when the Kremlin had forcibly annexed the nation in 1940, arrested and shipped its citizens to the Gulag prison camps, tortured and killed those opposing Soviet rule, subjugated its population to extreme poverty and ruled them by instilling fear in every aspect of their lives?

On January 13, 1991, Soviet troops attempted to overthrow the Lithuanian government led by Vytautas Landsbergis in the attempt to secede from the Soviet Union. During the attack to seize the TV Tower in Vilnius to create a media blackout, Soviet special forces killed 14 and injured over 700 unarmed Lithuanian citizens serving as human shields.

When Soviet tanks arrived at the Lithuanian Parliament building to depose the government, they were met with 30,000+ unarmed citizens singing songs and were forced to turn around.

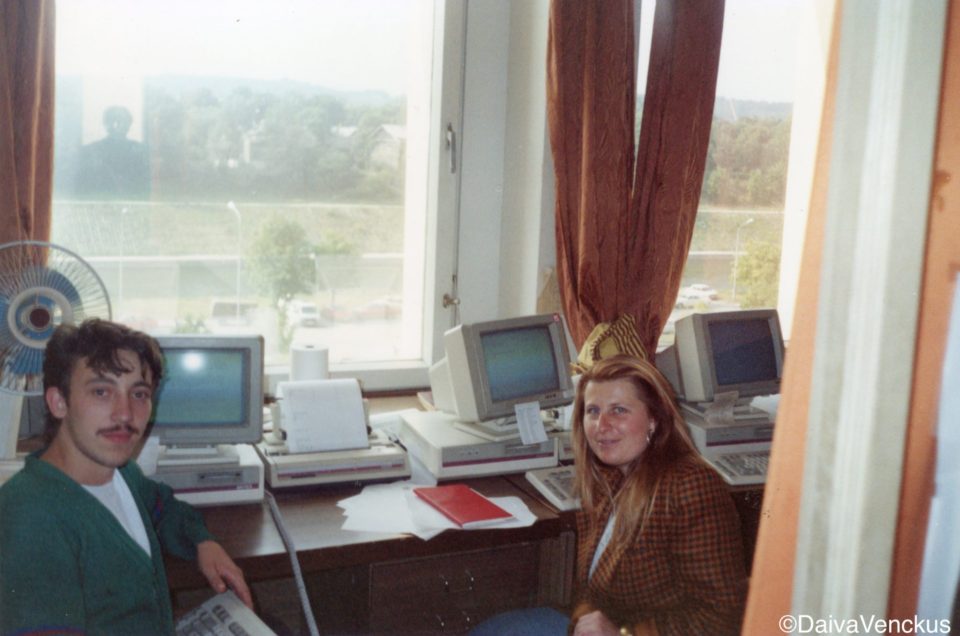

I was a 25-year old American-Lithuania. I moved from Los Angeles to Lithuania in January 1991 to help the cause and ended up working inside of the barricaded Parliament’s InfoBureau (Press Office) fighting to counter Moscow’s lies.

For eight months, a standoff between Vilnius and Moscow occurred—while the Soviet military occupied over 29 buildings (radio/tv centers, transmission towers, police stations, banks, etc) in Lithuania and attacked customs posts on its borders. On July 31, 1991, Soviet OMON forces shot eight Lithuanian volunteer border workers execution style in the middle of the night.

Soviet APCs guard the Vilnius TV Tower. The retaining wall show bullet holes and scars from the attack of January 13, 1991. (photo: D.Venckus)

On August 19, 1991, Gorbachev was held hostage in Crimea while his Neo-Stalinist leadership attempted to take control of the USSR by means of a coup d-etat. Their goal was to end the break up of the Soviet Union. By the morning of Aug. 22, 1991, the Putsch was over and Gorbachev had returned to Moscow. But who was in control?

In Lithuania, it seemed the Coup was over while Soviet troops were withdrawing from the buildings they seized during the August Putsch.

However, as long as the Vilnius TV Tower and other buildings in Lithuania seized in Janauray were occupied by Soviet forces, a Coup d’Etat was still in effect in Lithuania.

Gorbachev allowed these crimes to occur.

Was Gorbachev ready to allow Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia to become free and independent nations – or was he going to continue the military aggression he condoned during its continued illegal occupation of the Baltic nations?

On the morning of August 22, 1991, Parliament Chairman Vytautas Landsbergis called USSR General Moisejev and informed him if Soviet troops did not withdraw from the buildings that were seized by the Soviet military since January today, August 22, 1991, that Lithuanians, both citizens and volunteer forces, will take the buildings themselves. He left that open to interpretation.

Having survived the previous eight months in a country under siege was nerve-wracking enough, but now this ultimatum meant possible greater violence than the Lithuanian people had experienced in previous months.

And it would be the first time during the non-violent campaign of civil defense inspired by Sajūdis (Independence Movement) in 1988 Lithuanians might actually fight back with physical force.

In the morning, volunteer guards mobilized and were running through the hallways of Parliament preparing for the consequences of our ultimatum.

Thankfully, at the last minute, Landsbergis received a call from a Soviet Colonel, that the Soviet military would begin withdrawing from the seized buildings. It felt like we’d dodged a bullet, but we couldn’t believe it was actually going to happen.

After 50 years of the brutal Soviet occupation, would the Soviet military really withdraw?

My InfoBureau boss, Rita Dapkus, allowed me to leave the busy office inundated with calls from journalists to confirm and witness what might happen at the TV Tower.

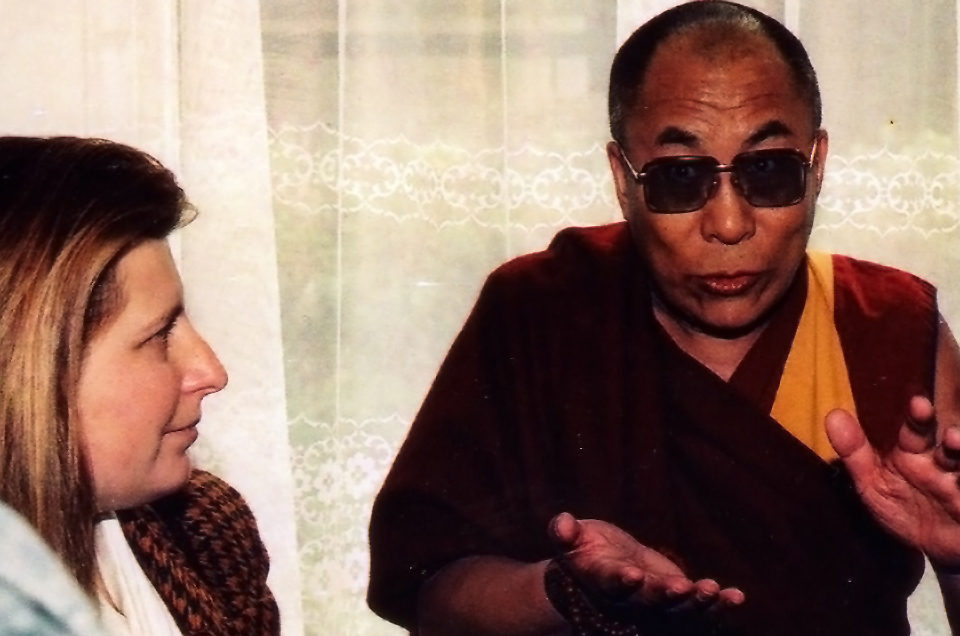

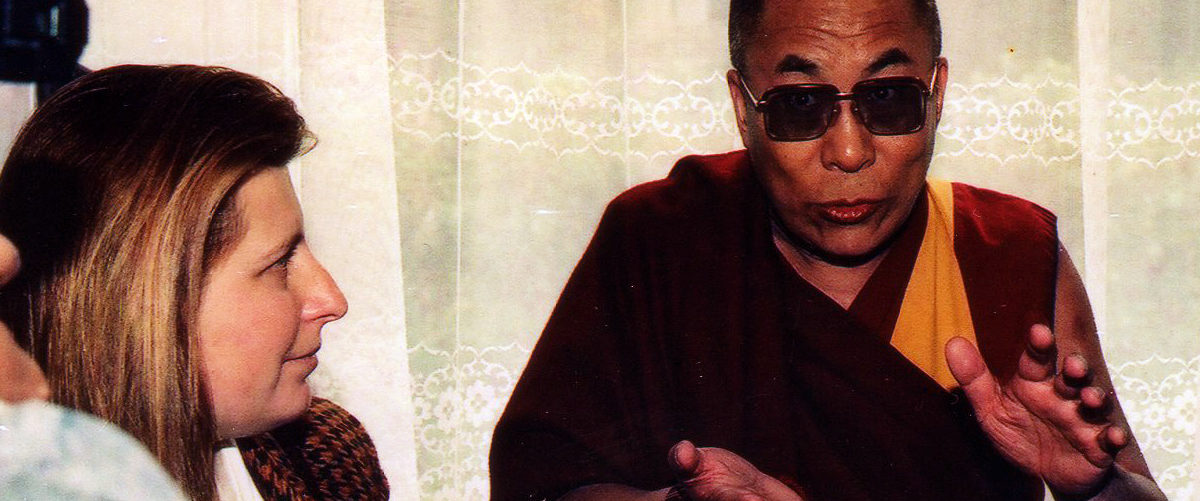

Rita Dapkus, a Lithuanian-American who established the InfoBureau Press Office at the Lithuanian Parliament who worked selflessly to counter Soviet propaganda and get the truth out to the world. (photo: D.Venckus)

I arrived at the TV Tower at 4:15 p.m. and worked my way through the crowd of tens of thousands toward the Tower complex main gate. Along the way, I ran into many foreign journalists who’d just arrived from Moscow.

When the journalists recognized me as an employee of the Parliament’s InfoBureau (Press Office), since I helped organize the many press briefings and helped with translating, they pulled me in multiple directions to help them with on-the-spot translations interviewing the crowd.

Each person we spoke to was in a state of disbelief. Tears formed in their eyes with the possibility the Soviet military may actually withdraw from the TV Tower. But the rising emotions in all of us weren’t about this one structure. This tower had become the symbol of freedom. If the tanks withdrew, then it meant they’d withdraw from Lithuania itself. That the Kremlin finally surrendered to the will of the Lithuanian people.

I easily found a friend, Edis (who worked at Sajūdis), in the huge crowd.

He was standing alongside of the road near the main gate with a bullhorn in hand directing the crowd, “When the vehicles leave, turn your backs to them and remain silent. Turn your backs to them. They do not deserve the respect to be acknowledged. Turn your backs to them …”

Finally at 6:07 p.m., the gates of the Tower complex opened.

A Soviet military column of six trucks and two jeeps inched past.

The thousands who gathered, as if a choreographed dance routine, turned away from the military column and stood frozen in silence.

We were one, in spirit and final rebelliousness.

Lithuanians had more than enough justification to express hatred toward the Soviet military; however, the principles of passive non-violent resistance had spiritually guided the Lithuanian people through their difficult struggle for freedom—to victory.

A British journalist standing next to me whispered, “I’ve never witnessed anything like this. This is the most powerful moment of defiance I’ve ever experienced.”

This is what it means to be Lithuanian, I thought.

I listened for the vehicles to drive past until I couldn’t hear their engines any more.

Gradually, as a group we turned around.

Members of the Lithuanian Security Department dashed through the gates. They raced toward the two-story administrative building. The security guards quickly materialized on the roof and pulled down the red hammer and sickle flag waving at us.

The crowd thundered with shouts of joy and cheers.

The impossible had happened!

When the guards dramatically replaced the Soviet flag with the Lithuanian flag everyone chanted in perfect unison, “Lietuva! Lietuva! Lietuva!”

Lithuania was actually free!!!

The multitude was out of control expressing joy.

People were hugging each other.

Others were jumping up and down chanting.

Someone linked arms with me, spinning me around, lifting me off the ground.

Some stood motionless with tears running down their faces.

I was crying, laughing and chanting at the same time.

Foreign journalists got caught up in the excitement and joined in the chanting, “Lietuva!”

I was swept up in the celebration, hugged and kissed and danced with the crowd.

While we celebrated, a Lithuanian Parliamentary delegation made their way toward the TV Tower along a worn path. People surrounding the perimeter of the fence clapped and cheered them on. There must have been about thirty thousand people in the crowd.

At 6:30 p.m. after celebrating with the journalists, a member of the BBC crew asked me, “Can you get us into the TV Tower?”

“I’m not really an important person with that kind of authority,” I said, “But I guess it doesn’t hurt to ask.”

I approached the Parliamentarians standing by the gate. They recognized me as an employee of the InfoBureau and greeted me with a smile.

I pointed, “This BBC crew would like to be able to go inside the TV Tower to shoot some footage.”

“Hmm. I’m not sure,” thought the Parliamentarian.

“Why not?” I asked.

“Well, I’m not sure.”

“Wouldn’t it be a good idea for the world to see for themselves that the Soviets actually left the TV Tower? That Lithuania is finally and truly free? Imagine the look on Gorbachev’s face when he watches BBC tonight.”

“That’s true. Wait a moment. I’ll find out if it’s all right for them to come in.”

He excused himself and walked up the path to the TV Tower and was cheered on by the crowd lined up along the fence.

After ten minutes he returned, “Yes, the BBC crew can come in, but only if you escort them and keep an eye on them. Miss Daiva, don’t let them touch anything.”

“Uh, shouldn’t the security guys escort them?” I asked.

“No, they don’t speak English. You know how to deal with foreign journalists. They’ll listen to you.”

“Uh, all right, I’ll keep an eye on them.”

The BBC crew stood off to the side waiting for an answer. I turned to them and gave them the thumbs up. They smiled a “thank you’ and approached the gate. The Parliamentarian opened it and pointed at the path, “Go ahead.”

I was overwhelmed and filled with emotion by the fact that I was entering the Tower complex. After all these months looking at the Tower from outside of the fence, from across the horizon from the InfoBureau windows, here I was, inside.

Daiva stands on the barricades on the bridge near the Parliament building that stopped the tanks on August 19, 1991. The TV Tower is in the far distance. (photo: D.Venckus)

“Follow me,” I instructed the BBC crew with authority, as if I knew where I was going.

As soon as we entered the courtyard of the administrative building, people cheered and clapped. I didn’t realize so many people, thousands, more surrounded the perimeter of the Tower grounds. They cheered louder and waved at us.

I was embarrassed.

I wanted to yell back at them, “It’s only me. No one special. Nothing to cheer about here.”

The BBC crew were glancing at each other, wondering and feeling the same.

It didn’t matter.

The Soviet military were gone.

All us Lithuanians helped make this happen.

There were those who gave their lives on this very ground on January 13, 1991. Those who served as human shields at Parliament whose sheer numbers forced Soviet tanks to turn around. Inside of parliament, workers who informed the world of what had occurred and countered Moscow’s propaganda each day. Landsbergis and other government leaders who voted to re-establish independence and fought for international recognition. In the past decades, the dissidents, the partisans and those who died in Siberian Gulag prison camps. The emigres who escaped and never forgot the Homeland and lobbied the governments of their adoptive countries.

We should be cheering each other!

I gave the crowd a victory sign in the air while we continued up the path.

They yelled louder and waved.

The BBC crew got into the spirit and waved back at the crowd.

I threw both arms in the air, spun around and waved the victory sign to everyone.

The crowd chanted, “Lietuva! Lietuva!”

I chanted along, shaking my fist in the air and laughed with the BBC crew to the base of the TV Tower.

We met the Lithuanian delegation at the doors.

“The film crew may be allowed inside once we access the situation,” the Parliamentarian said.

“That would be great,” I said, “How long will it take?”

“We’re concerned about potential booby traps and want to do a quick clean sweep of the floors first before civilians were allowed in. Not long,” he replied.

I conveyed this to the BBC crew who prepared their cameras. The delegation entered the building. While the BBC crew filmed around the base of the Tower, an eerie feeling came over me.

Eight months ago, on January 13th, this was a battlefield.

In my mind I saw the images from that night.

The tanks.

People linking arms.

The gunfire.

The flashes of light.

Soldiers beating people.

The victims.

I now stood where Soviet soldiers stood just minutes ago.

I scanned my immediate surroundings for any evidence of the battle that took place.

I saw tank treads, zig-zagging and crossing over each other, all over the packed dirt surrounding the Tower.

Dark defined marks and streaks scarred the Tower walls.

Bullets.

Most of the windows of the Tower lower level were broken or cracked. The shattered windows were boarded up from the inside with various pieces of wood and rags.

The BBC crew was filming the complex plateau when a Parliamentarian appeared at the Tower entrance door, “Miss Daiva. You may come in. Please tell them not to touch anything. This is a crime scene.”

The BBC crew rolled their cameras while we entered. It was exactly 7:00 p.m. when we crossed the threshold.

The first floor of the TV Tower was a disaster. The floor was destroyed. The soldiers pulled up parts of the floor.

The soldiers had to endure the Lithuanian freezing winter with the rest of us with Moscow’s imposed economic blockade. Everywhere there may have been wood, there were holes and gaps. All the furniture was gone. Busted glass from the windows sat swept up in piles up against the wall. The place smelled worse than those awful Russian piparosa cigarettes. It was dark and dingy like a post-apocalypse gym locker room.

We made our way to offices on the third floor where we came across a heavy, solid door. When we opened it, a bright light filled the staircase. A huge potted palm tree with leaves scraping the ceiling unexpectedly greeted us. The room was surprisingly nice. We entered a large, bright, open room with studio control equipment and monitors surrounding us. From all of the monitors, Gorbachev was lecturing at us.

I assumed they were tuned into Moscow TV, broadcasting Gorbachev’s appearance before the Supreme Soviet earlier that day. Gorby didn’t look very happy. He didn’t realize it yet, but he was no longer in charge.

One of the BBC journalists joked, “Looks like they didn’t have it too bad here.”

They began filming. We wandered through the floor. The studio equipment was intact and in working order. Nothing appeared to be damaged. I helped the BBC crew with translations while they interviewed the Parliamentarian delegation.

After the interview, the BBC crew and I continued down a hallway lined with doors, which we opened to find offices converted into sleeping quarters. Out of the window of one of the rooms I saw a familiar building on the horizon. The Lithuanian Parliament building loomed in the distance.

For many months I stared out of the fourth floor InfoBureau windows at the TV Tower on the horizon. I often contemplated whether the soldiers ever gazed out of the Tower’s windows and wondered if anyone was staring back from Parliament.

I imagined the soldier who looked out this window at us, while I was staring out of the InfoBureau windows at him. Both of us didn’t know how this was going to end. Although I never met the person who occupied this room. I knew he was just a young draftee following orders. I was just a girl from America who wanted to help Lithuania.

I certainly didn’t think I’d be standing on the third floor of the TV Tower staring out at the Parliament building minutes after the military retreated, the exact moment Lithuania truly became free.

Tears welled up in my eyes.

How in the world did I get here?

Of all people why me?

My dad used to tell me we need to witness history with our own eyes so the truth cannot be erased.

My Los Angeles Lithuanian community (along with every other émigré community) battled the decades of Soviet lies by teaching my generation the truth about the Soviet occupation of Lithuania—although, the rest of the world seemed to have forgotten Lithuania existed.

Sharing stories of the past, of our ancestors, was a Lithuanian tradition. But in this age of historical revisionism, these stories were the only link, the proof the Lithuanian nation was a truth.

I never dreamed I would witness Lithuania’s freedom with my own eyes.

In that moment I understood, it’s my destiny to share the gift I received as a witness to these events, to remind Lithuanians and the world in the future, who we Lithuanians are – so that no one can attempt to erase the Lithuanian nation again.

Gazing out the window I was relishing in my glorious happiness, reaching a state of complete enlightenment.

Then I noticed a phone on a small table under the window.

I lifted the handset to see if it was working.

It was.

I dialed the number to the InfoBureau.

Rita answered in our standard greeting, “’Ello, InfoBureau.”

“Rita, it’s Daiva.”

“Where the hell are you?”

“Guess where I am.”

“It’s super busy here.”

“Look out your window. Guess where I am.”

“Wherever you are we need you back here.”

“Rita,” I said with the greatest pride, “I. Am. Inside. Of. The. TV. Tower. On the third floor. Looking out a window at the Parliament building. At the windows of the InfoBureau.”

I waited for her to acknowledge this momentous, historic moment, but Rita was all about business, and said, “That’s great. Daiva when can you get back here? The building is swarming with journalists and the phones are ringing off the hook.”

I snapped out of my moment of patriotic glory.

I didn’t have to make the moment last—a single moment can last forever.

I lived to see a free Lithuania.

And so will everyone from now on.

No more Soviet lies.

No more Lithuanian victims.

And Rita was right, the real work to help a new democratic republic emerge was just beginning.

To this very day Moscow continues to attempt to undermine Lithuanian independence from cyber-hacking to military incursions into Lithuania airspace. The Kremlin conducts military exercises on the borders of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia and conducts propaganda warfare by rewriting Lithuanian history and making wild anti-Western claims to sway public opinion.

History does repeat itself.

In 2014, Russia illegally annexed Crimea, in a similar manner they annexed Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia in 1940.

Russia is waging a war in Ukraine.

Moscow’s tanks and lies continue to inch closer to destroy democracy across the world each day.

Witnessing the moment of a nation’s freedom should not be a historical event. The citizens of all nations should be enjoying freedom each and every moment of each day.

Therefore, all of us, not just Lithuanians, need to remain vigilant, to weed out the truth and promote it to ensure liberty and freedom for all peoples.

Witness history with your own eyes.

It’s happening right now.