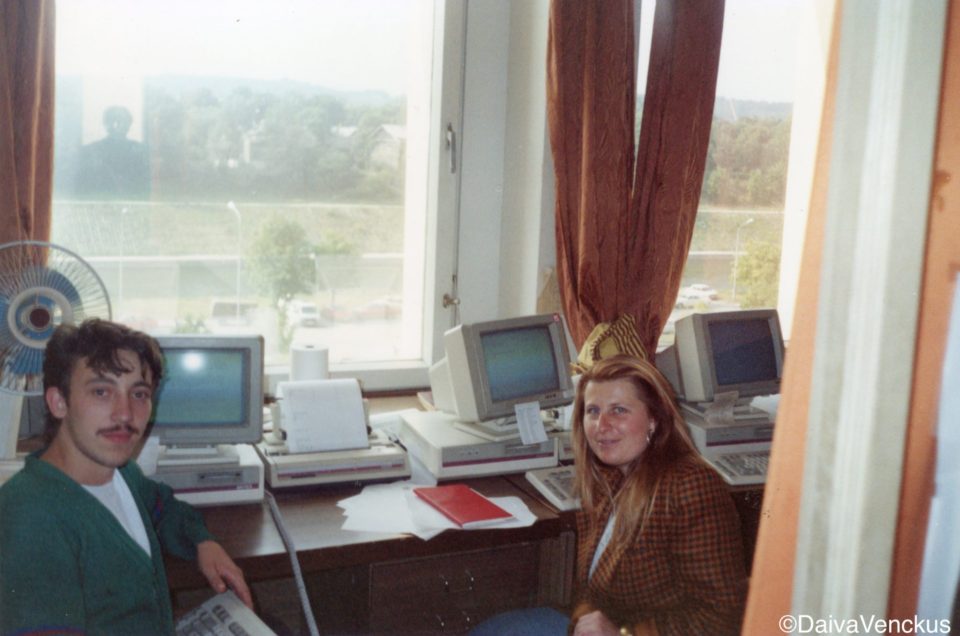

I once asked my boss, Chicago-native Rita Dapkute, several years after we both both worked at the Lithuanian Parliament in the Press Office (Information Bureau) during the period when Lithuania was trying to break away from the Soviet Union, “What event was more scary? January 13, 1991 or the 1991 August Coup?” Both events saw Soviet tanks approach the Vilnius Parliament building in the attempt to seize it—and Rita experienced both while barricaded in the Parliament building. Rita had been in Lithuania since the start of Sajudis and had experienced it all.

Rita replied, “The 1991 August Coup was more scary –because on January 13th, we didn’t expect the Soviet military to attack with the violence they did and kill and injure so many. We were in too much shock to understand what was happening. After January 13th, we understood what the Soviet military was capable of, and we feared a similar attack and more bloodshed.”

I watched the events of January 13th, 1991, safely from the comfort of my parents’ home in Los Angeles. As the images of the Soviet military attacking unarmed Lithuanian civilians as they seized the Vilnius TV Tower filled the television screen, my parents confronted me, “You can’t think about going now!”

I was to board a plane to Riga, Latvia on January 14th. My grandfather’s friend was to pick me up from Riga and drive me to Kaunas, Lithuania. I’d spent my entire life learning about my ancestral heritage and was raised to to believe it was my duty to help preserve it. I’d participated in Lithuanian scouts, Saturday School, folk dancing and was president of the youth association –but I wanted to do more. I wanted to live in Lithuania, experience my culture first-hand, and I’d decided to move and live there for several years.

My family and friends attempted to talk me out of going, to wait until “things calm down.” But I thought, What can I do to help in Los Angeles? Isn’t this the time that Lithuania needs help the most? I am nobody special, but I can show up and help somehow.

I don’t believe many parents would be supportive of their 24 year-old daughter flying by herself into the heart of a revolution, especially one day after 14 people were killed and over 700 injured—but I inherited their passion for the homeland, therefore, they understood why I was compelled to continue with my plans and they gave me their blessing.

After landing on the deserted snow-covered tarmac of the Riga airport in the late afternoon of January 15th, 1991, and undergoing an absurd interrogation from Soviet customs officials trying to explain my two-year supply of shampoo and other supplies, I found my ride, Tomas, waiting for me in the waiting hall. He drove from Kaunas to Riga and explained he honestly didn’t want to pick me up because he didn’t know if it was safe to make the journey, but he’d promised my grandfather he wouldn’t leave me stranded.

As we departed the airport through the deserted Latvian streets in his LADA Zhiguli, I asked Tomas if everyone was hiding since Moscow had just declared Martial Law in the Baltic states. “On the contrary,” Tomas informed me, “700,000 Latvian citizens are building barricades in Riga’s city center, preparing for a similar Soviet military action, like what happened at the Vilnius TV Tower.” The bravery of the Latvian people struck me, as they had seen the violence the Soviet military had perpretrated in Lithuania and were aware they may experience a similar attack. (A few days later, On January 20th, Soviet forces would act, seizing buildings and killing three Latvian civilians.)

We drove in silence through the abandoned streets of Riga onto the dimly lit main highway. I was expecting to see Soviet military columns, but we were the only ones on the road. After an hour, the car entered a brightly lit part of the highway. “This is the border,” he said. A brick customs building was lit up under a bright streetlamp past the forest clearing. The tollbooth was deserted. The structures were dark.

“Where’s the border checkpoint?” I asked.

“This is it. It’s strange that no one’s here. We’re not stopping.” The glare of a shiny object ahead struck my eyes and morphed into a new road sign bearing the words: Lietuvos Respublika. My heart skipped a beat as we drove past. I’m here. I made it.

We drove past an abandoned Lithuanian customs post on the other side of the border. The car rumbled through villages and towns between breaks of forest and fields. Snow covered Lithuanian flags glistened in the light of the street lamps. The yellow-green-red flags hung from windowsills, doorways, draped over fences, from tree branches and even covered rooftops.

When I visited Lithuania for the first time in 1989, I was swept up with the excitement of the “Singing Revolution.” The Lithuanian flag, banned for four decades but newly legalized, was everywhere: in windowsills and hanging from streetlamps, in the form of stickers on dashboards of cars, on Sajudis billboard notices anouncing the next demonstration, and on pins on jacket lapels. After two years those displays of patriotism had multiplied, but was now more meaningful, as its fate, Lithuania’s freedom, was now uncertain.

As we drove into larger towns, dozens of people stood around campfires in front of official-looking buildings—some held flags, others, placards. In one remote village two old men stood in the dark holding a protest sign in front of a building the size of a garden shed. My ride didn’t need to explain what these people were doing out in the freezing snow. I understood they were serving as human shields. These may have been local Lithuanian Defense Ministry offices or radio outposts the Soviet military might target. And no one was armed. The Lithuanian revolution was based on the Gandhian principles of non-violent resistance.

I thought, Who did they think would see their protest? We were the only people on the road. What would happen if Soviet soldiers decided to seize these buildings? Who would ever know if they were arrested or killed? They’d just disappear into the night just like people did in Stalin’s time.

An hour past the Latvian border, around 8:30 pm, we reached Lithuania’s fourth largest city, Siauliai. We pulled up to the city center square. Thousands of people surrounded enormous bonfires. Tomas suggested we warm up by the fires, as his LADA didn’t have a heater and the temperature was in the negatives. The car was only slightly thicker than an aluminum soda can. The only hotel in the city had opened up its doors for people to warm up and use the restrooms and have a cup of tea.

This picture is from January 27, 1991 – at Vilnius Parliament – representative of the brave regular unarmed citizens serving as human shields around the clock against a Soviet military attack. (photo: D.Venckus)

In front of the hotel, a bonfire raged over our heads. People huddled together, talking. Some were singing silently to themselves. Little kids darted through the crowd. Elderly women clutched rosaries in their faded wool gloves whispering prayers. Others held flags or signs. Standing before the flames, a warm wind brushed across my face as I stared at the faces of uncertainty. A wave of empathy took over my emotions. The revolution was no longer about singing patriotic songs. It was about life and death. Now that I’m here what am I supposed to do? If the Soviets start arresting Lithuanians and send them to Siberian prison camps, I can always leave. These people can’t. Why are they putting themselves at risk by protesting out in the open like this?

After January 13th, you’d think everyone would be hiding in their homes, scared to come out. But no, on that entire stretch of highway two hundred miles from Riga to Kaunas thousands of unarmed people were out in the cold, in the streets, protesting and protecting possible targets. They knew perfectly well what the Soviet military was capable of. I realized that Moscow was probably now more terrified of that Lithuanian spirit of unity and defiance than anything else – it was that very unity and defiance, of thirty-thousand unarmed civilians singing songs, that was more powerful than Soviet military steel and prevented the tanks to take the Parliament building on the night of January 13th.

We reached Kaunas at 10:30 p.m. at Tomas’ mother’s apartment near the city center. We barely knocked on the door when Birute opened it and said, “Thank goodness you made it! Both of you!” She wrapped me in a hug. I’d met Birute druing my 1989 visit. Her family helped save my grandfather’s family back during WWI. They maintained their friendship throughout the last 80 years—and Birute promised my grandfather to watch out for me, and get me out of the country if it came to that.

Birute gestured toward her living room sofa and a plate of standard Lithuanian hospitality: tasty black-bread-butter-sausage-cucumber-tomato sandwiches.

Birute turned on the television. It was just past 11:00 p.m. She yelled at the screen, “It’s Kasperavicius! What lies do you have for us now?” She explained the Soviet military occupied TV Tower in Vilnius was broadcasting with a new pro-Moscow crew—filling the airwaves with Moscow’s propaganda.

Birute pointed at the TV, “He’s one of the putsch leaders! He’s responsible for the attacks, for the deaths at the TV Tower! They go on the air and broadcast they’ve saved the country from the threat of Sajudis—when it is THEY who’ve brandished weapons and killed innocents!” She shook her fist at the screen and yelled, “LIAR! LIAR! LIAR!”

I understood why my grandfather entrusted Birute to take care of me. I think she would’ve gladly entered a boxing ring to take on Gorbachev herself.

My head was pounding with the images of the attack on January 13th that occurred less than 48 hours before. Will the people I saw guarding buildings be the next victims? Why the hell did I think this was a good idea? My life of Lithuanian Saturday School and folk dancing and scouts did not prepare me for this—a bloody REVOLUTION.

This was truly a revolution of the people. The entire country had mobilized, from border to border, in the cities, towns and villages, and each person was doing their part—continuing to serve as unarmed human shields, with the complete awareness their lives could be in danger. I kept thinking, They know what could happen? Why are they still out there and willing to stand before tanks?

Eight months later, during the 1991 August Coup, with my own eyes I’d see those same unarmed Lithuanian civilians, run towards Soviet tanks as they approached the Lithuanian Parliament building. And I’d think, They are all going to get killed!

Rita was right, each day after January 13th was scary, because we knew the Soviet military was capable of more bloodshed. They did kill again. On July 31, 1991, eight Lithuanian border guards were shot execution style by Soviet OMON forces in the middle of the night. Only one survived.

On January 13th and July 31st we remember the martyrs, the heroes, who gave everything, their lives, for Lithuania’s freedom.

And to this day, I also think about the thousands of people, those Lithuanians who continued, day after day, week after week, to stand guard and wait for the Soviet military to attack. Lithuania is free today because of every single person who took a stand against Moscow. Each individual made a difference. Not only on January 13th, but in the months that followed, Lithuanians never wavered in their unity and defiance.

Gandhi had said,”First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win.” I am still in awe of how a tiny nation took on the Russian bear with the utmost dignity and integrity and tore down the entire Soviet Empire. After twenty-five years, Lithuania is still winning.