In Lithuania, on January 13, 1991, the massacre at the Vilnius TV Tower proved a turning point in Lithuania’s struggle for freedom. Once blood was shed, the rules had changed, and the stakes raised.

On January 16, 1991 I witnessed the funeral for a martyr of the great cause of Lithuanian freedom. I was a 24 year old American-Lithuanian, the daughter of WWII displaced persons. I left Los Angeles on Janaury 14th, a day after the Soviet attack at the TV Tower. I bought my one-way ticket months in advance and chose to travel to Lithuania despite what occurred at the TV Tower. I arrived in Lithuania through Riga, Latvia on the 15th. On the morning of the 16th, I was in Kaunas and attended the funeral procession for one of the victims: Titas Masiulis.

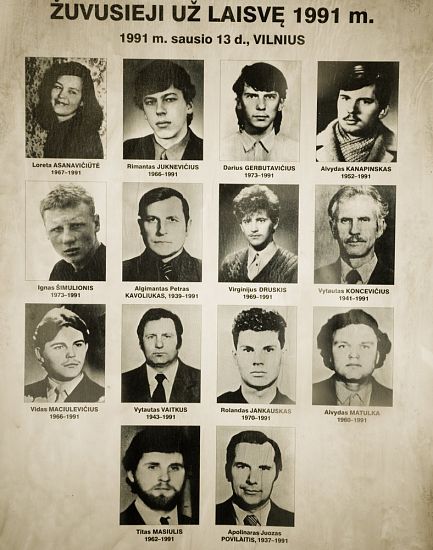

Fourteen people had been killed at the TV Tower, and the victims received state funerals in Vilnius with over a million citizens in attendance. One of the martyrs, Titus Masiulis, was a Kaunas native and was to be buried in the local cemetery.

In the days before the funeral, the bodies of the victims were laid in the Vilnius sports arena in open caskets. Over one million people (out of a population of 3.5 million) lined up to pay their respects, to see the faces of the martyrs with their own eyes. Lithuanian history had been rewritten by the Soviets; therefore, it was important for Lithuanians to witness this history personally, so if need be, they could tell the next generation the truth. My entire childhood growing up in Los Angeles was filled with family stories about their escape from Soviet occupied Lithuania and the illegal annexation of the Baltic nations. The lies from Moscow had continued for decades, and no doubt, the Kremlin would lie about their own crimes in Lithuania in 1991.

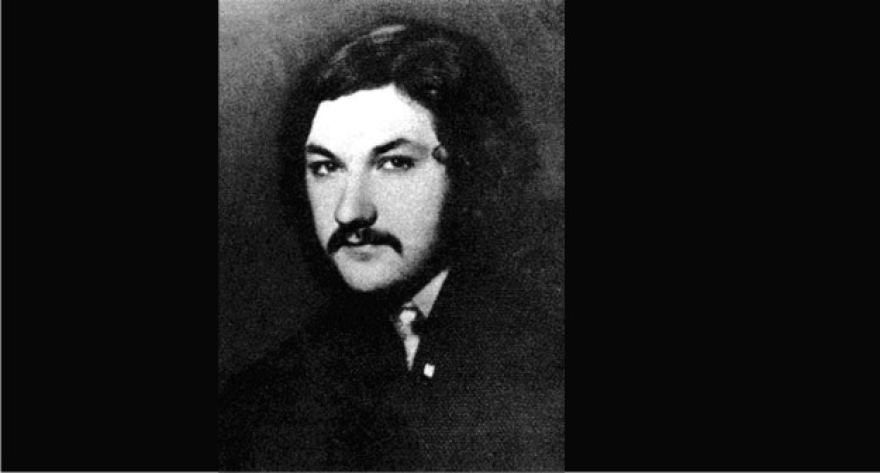

This is what the face of a human shield, a martyr looks like:

Titas Masiulis (1962-1991)

Just a regular nice guy who enjoyed hiking—a 28 year old tried to make his way through the world with an ordinary job, who probably thought about starting a family some day. He actively attended Sajudis demonstrations, because it was the right thing to do—to want freedom.

On January 13th, no one planned on being a hero, a martyr. After Communist Party organized groups tried to storm the Parliament building on January 8 and the Soviet military violently seized the Press House on January 11 and other buildings, unarmed citizens served as human shields at various buildings that were Moscow’s targets: the Parliament building, the Radio/TV center, transmission towers, the main TV Tower in Vilnius. People became heroes because when the Soviet military showed up, instead of running away, they linked arms and sang and chanted, refusing to let them pass.

On January 13th at the Vilnius TV Tower, Titas died from multiple gunshots to the chest.

Soviet President Gorbachev blamed the violence on “radicals” who provoked and fired upon the Soviet forces. These “radicals” were unarmed citizens like Titas, who participated in peaceful protests at the TV tower, singing songs around bonfires. They didn’t plan on becoming human shields. The only people who had weapons were the Soviet military. There would not have been any violence if Soviet forces didn’t show up with tanks with the intention to seize and occupy the TV Tower.

On the morning of January 16th, in Kaunas, I made my way toward the funeral procession route through the crowd of hundreds of thousands to a building with a set of wide steps. People made room when I squeezed in. I swayed back and forth when others pressed their way onto the sidewalk and stairs. A teenager behind me placed his hand on my shoulder to ensure I wasn’t pushed off the edge. I placed my hand on the shoulder in front of me. An ancient wrinkled face under a wool scarf turned to me and smiled.

Packed in tight among thousands of bodies, the vibrations of those breathing and speaking around me permeated my skin. I caught shadows of the whispered conversations of those around me. The details of that fateful night were still coming in. There were unconfirmed rumors. An air of confusion in the turmoil of events created fear and uncertainty for the future. I listened as people speculated and conversed:

“50 people were killed, not 14.”

“I heard that others were carried off by the soldiers.”

“People are still missing.”

“The youngest victims were only 17.”

“Did you hear that Loreta is being buried in a wedding dress?”

“I went to the casket viewing and saw her in the wedding dress. Poor girl. Dead at 23. Run over by a tank.”

“I heard when she was brought to the hospital she was still conscious and asked the doctor, ‘Will I still be able to marry.’ That’s why her family is burying her in a wedding dress.”

I just about lost it. 23? I was going to be 25 in March. I didn’t want to listen anymore. My head throbbed. My toes were frozen in my cowboy boots.

While I glanced around, I wondered how many of these same people attended another such funeral on this very street, for another martyr, 19 years prior—for Romas Kalanta. In 1972, 19 year-old Kalanta set himself on fire, by pouring gallons of gasoline over himself in a public Kaunas park, to protest the Soviet occupation of Lithuania. He left a simple note: “blame the regime for my death.” Attending Kalanta’s funeral turned into an act of civil dissobediance, when Soviet authorities tried to prevent people from attending it. Thousands, mostly youth, marched in protest—many were arrested and sent to prison.

Romas Kalanta (1953-1972)

As many as eleven others had self-immolutaed themselves in protest of the Soviet regime. Their names have been lost to history like so many who had been killed during WWI and suffered in the gulag, the partisans, and others who disappeared in the night by the hands of Soviet authorities. The Kremlin too called these victims “radicals.”

Lithuanians worldwide are commemorating 2018 – a significant year – the 100 year anniversary of the restoration of Lithuania. It was on February 16, 1918, when Lithuania restored independence, ending Czarist Russian rule. Over the decades since 1918, thousands of Lithuanians have been erased by the Kremlin, but today on January 16th, the names of these heroes would not be forgotten – and the memories of those victims from the past would fuel the independence movement.

I looked around, wondering if the Soviet authorities would prevent people from attending Titas Masiulis’ funeral. Lithuanian government leaders and dignitaries, along with a million citizens were at the funeral in Vilnius. But, here in Kaunas, the more intimate event of tens of thousands could be a good target for Soviet forces.

In the distance a single church bell began to chime to the timing of a heart beat. My own heart aligned with the bell. Squeezed in with the crowd, I could feel everyone’s heart beat in unison. A hush fell over the masses. Necks stretched to catch a glimpse of the procession.

The funeral procession in Kaunas for Titas Masiulis, a victim of the January 13, 1991 Soviet military attack at the TV Tower

Marching stepped in rhythmic pace of the church bells, the procession was led by clerics carrying religious symbols, flanked by altar boys carrying tall banners of the Virgin Mary and a crucified Jesus. Following them, were girls carrying candles and flowers dressed in traditional Lithuanian costumes .

The cold air was lifeless. Even the trees that lined the streets with gnarled branches strangled by winter reached toward the sky seeking a breath of air. Two men in suits held a framed portrait of Titas. A strong face with piercing eyes and a full beard. He was extremely handsome. A group of a dozen people clutching Lithuanian flags followed.

The casket of Titas Masiulis, victim of the January 13, 1991 Soviet military attack at the TV Tower

When the dark wooden casket draped with a Lithuanian flag appeared on the shoulders of several burly men, a tsunami of sobs reached me as it traveled through the assembled mass of bodies. His remains were treated like a government leader, not an ordinary citizen. My tears shifted back and forth from sadness to anger, while I grinded my teeth from the cold.

Once again, I thought, we can blame the regime for this death.

When the procession passed by, people filled the street shadowing the casket, proceeding to the cemetery.

At the cemetery, the flag-covered casket floated above the heads of the crowd. Thousands crushed in around the burial site. I was swept up in the slow moving crowd and propelled up the hill toward the burial spot. With my petite stature, all I could see were the backs of coats and knitted caps but I allowed the crowd to move me forward.

A telephone pole stuck out like a buoy from the sea of people. Two young men hovered over the crowd, clinging to its side. One reached down and tapped my shoulder and I instinctively raised my arm and next thing I knew I was floating upward to one of the men positioned on a rung above. I wrapped my arms tightly around the icy pole.

I had a clear view of the casket, about a hundred feet away, and the family wailing beside it. I wondered if Romas Kalanta was buried nearby. I’d come to Lithuania to connect with my ancestral heritage and I somehow now would become a witness to its history. My father had always told me that, “We must witness history with our own eyes,” because later, those who rule will lie about the facts. Just as Moscow had lied that Lithuania had willfully joined the USSR in 1941. Lithuanians knew the truth and refused to accept Moscow’s lies. That’s what this revolution was all about. To restore the truth. To restore Lithuania. And now we all had an important job, like my family who told me about what happened during WWII. My duty to Lithuania was to witness all the events so that we could tell these stories to future generations.

The crowd fell silent. A voice rose up and echoed. A priest talked and gestured. I couldn’t make out the man’s words. He was too far. The coffin was carefully lowered into the grave. I didn’t notice when I began crying. A song of mourning swept through the wave of the tearful multitude.

The sad singing lasted for a while, as did the cause for freedom. The Lithuanian people endured another eight months of Soviet military aggression before they finally broke free of Moscow.

You would think that after January 13th everyone would hide in their apartments in fear. Everyone knew what brutality the Soviet military was capable of. We witnessed the burial of the victims. We saw the images of the those killed and injured.

Gorbachev claimed he knew nothing and did not order the attacks, yet from January 14-21 Soviet troops attacked Latvian citizens in Riga, killing three. The Soviet military continued acts of aggression in Lithuania in the following months. Soviet checkpoints terrorized and detained citizens. Young Red Army draft dodgers were beaten and arrested. The Red Army occupied twenty-nine buildings during this time. On July 31, 1991, Soviet OMON forces killed seven Lithuanian border guards, execution style. Who was in charge of the military if Gorbachev “knew nothing” after each and every act of Soviet violence? The lies were never going to end.

People had every right to be scared and to hide. But they did not!!! After the January funerals of the victims, people returned to serve as 24-hour human shields at the barricades in Vilnius, at the Kaunas TV station and transmission towers, and in other parts of the country. Whenever there were new threats, unarmed citizens ran toward them.

That day on January 16, 1991 we may have buried the heroes, the martyrs who died for Lithuania’s freedom, but the truth was that Moscow would have had to kill every single Lithuanian citizen to successfully crush the cause for independence, because each and every Lithuanian was and is a hero – – – including those previous generations who suffered under Soviet tyranny and fought the lies of the past.

May we never forget each drop of blood lost, each tear shed for Lithuania’s freedom.