On the morning of July 31, 1991, I received a phone call that shakes my soul to this very day each time I remember it.

“Something horrible has happened. Come to the InfoBureau at once,” Arvydas said.

“I was just in the office, working the nightshift,” I said, glancing at my watch, which read 8:00 a.m., “Everything was fine. What could’ve possibly …”

“The worst thing imaginable happened. Come in right away,” he said with low, measured voice.

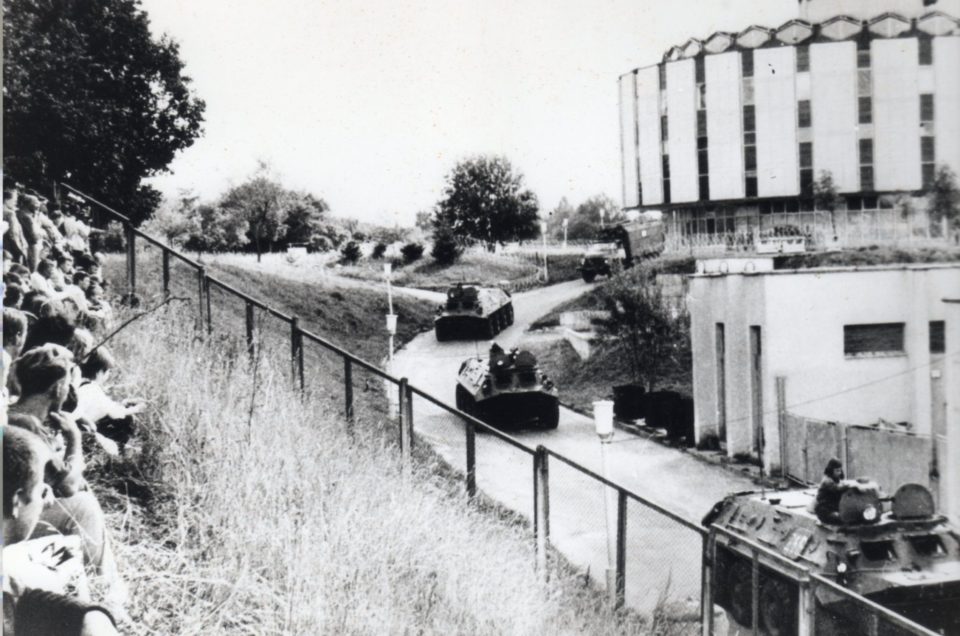

A year-and-a-half earlier, on March 11, 1990, Lithuania had re-established independence but Moscow was not going to let Lithuania become free without a fight. USSR President Gorbachev implemented an economic blockade against Lithuania in the hopes to strangle the nation into submission, but the Lithuanian government outmaneuvered the Kremlin and made deals directly for resources with neighboring Soviet republics. On January 13, 1991, Moscow sent in Red Army tanks finish the fight once and for all with a coup d’etat. During the seizure of the Vilnius TV Tower, Soviet soldiers killed 14 unarmed civilians and injured over 700 who were serving as human shields. Believing they’d successfully executed a media blackout, Soviet tanks arrived at the Lithuanian Parliament minutes later to complete their mission, but 30,000 civilians linked arms and sang patriotic songs, preventing the tanks from advancing. Ad hoc barricades were built around the building and remained as the last stronghold for independence.

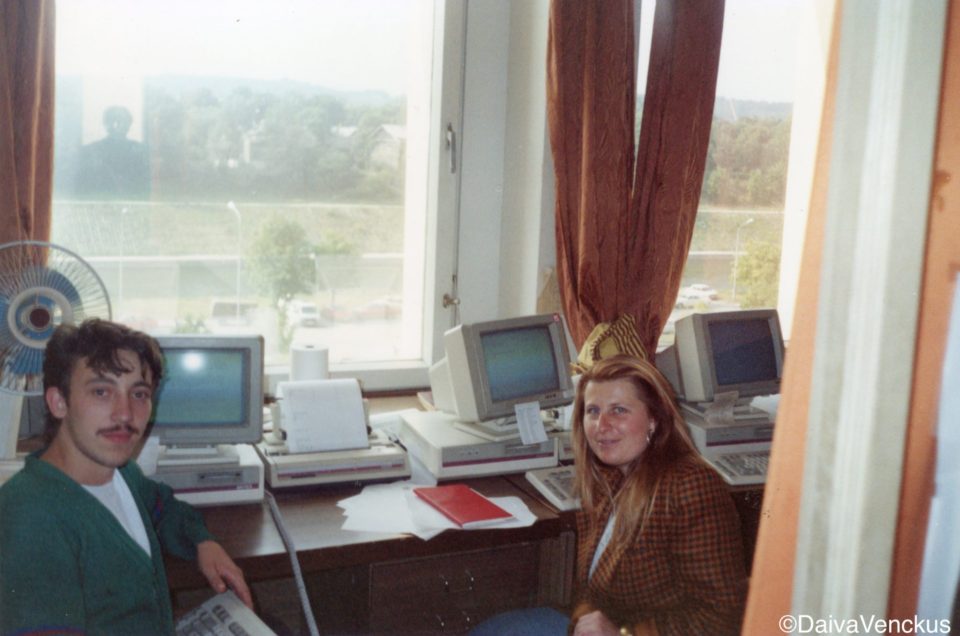

I was a 25 year old Lithuanian-American who arrived two days after the attack at the TV Tower, on January 15, 1991 and began volunteering for the cause for freedom. I ended up in the InfoBureau, the Lithuanian Parliament’s Press Office.

I’d left the office on July 31 at 4:00 a.m. because we were writing press releases and answering calls from journalists about the Lithuanian-Russian Treaty that was signed between Russian Federation President Yeltsin and Lithuanian Parliament Chairman Landsbergis in Moscow on July 30th, solidifying economic cooperation. From a legal standpoint, entering into this treaty, Russia and Lithuania acknowledged each other’s sovereignty. This undermined Soviet President Gorbachev’s efforts to keep the Union from falling apart. But U.S. President Bush was to meet in Moscow with Gorbachev on July 31st to secure his power at home and on the world stage.

However, the primary reason we worked night shifts, was because we feared Moscow’s forces would attempt to attack the Parliament building. In addition to our press relations responsibilities, the InfoBureau served as a citizen hotline to report Soviet troop movement and aggression. My job included gathering the information and passing it on to the Lithuanian defense department to assess threats to the Parliament building.

We’d been working 30 hour shifts, taking in calls about Soviet military units setting up checkpoints and harassing and detaining citizens, seizing telecommunications buildings and committing other acts of aggression. We got the facts out to foreign journalists.

When I arrived at the InfoBureau the morning of July 31, my co-workers were in Rita Dapkus’ office watching the television. Rita, a 29 year-old Lithuanian-American had established the Parliamentary Press Office when Lithuania reestablished independence. The foreign press had finally taken interest in Lithuania’s aspirations for freedom and the InfoBureau provided trustworthy information and fought Moscow’s propaganda.

My co-workers were watching a Lithuanian police crime scene videotape. The images on that screen would remain forever imprinted in my mind.

On the floor of a small room laid six men. Face down. In pools of dark blood. I recognized at once some of the men were wearing Lithuanian customs posts uniforms.

This was another customs post attack – but not like any other.

Since May 1991, the Soviet military had been engaged in almost daily attacks on Lithuanian customs posts. They’d harass, detain, beat up workers (who were always unarmed) and ransack the posts. These men were volunteers, not trained soldiers. Lithuanian workers did not retaliate during these attacks. I’d received a few calls during my nightshifts from frightened workers who’d endured attacks to report the incidents.

“Medininkai,” Arvydas informed me.

Rita sat at her desk, with tears forming in her eyes yet she remained stoic, shaking her head mesmerized by the TV screen. Another co-worker was sobbing quietly. I didn’t want to watch this horrible video, with the blood and the dead men, but I knew foreign journalists would soon be calling and I had a duty to describe what was on the crime scene tape. Through my own tears I tried to memorize all that I heard and saw.

“Eight men were shot in the head, execution style,” Rita announced, “The two survivors are in the hospital fighting for their lives.”

While the camera panned the floor of the bloody customs post, it was obvious the men knew what was coming. Some covered their heads with their hands, as if it would protect them from the bullets penetrating their skulls.

On Rita’s desk I saw a list of names:

Mindaugas Balavakas (b.1970) – 21 yrs old – killed

Juozas Janonis (b.1962) – 29 yrs old – killed

Algimintas Juozakas (b.1969) – 22 yrs old – killed

Algirdas Kazlauskas (b.1949) – 42 yrs old – killed

Antanas Musteikis (b.1958) – 33 yrs old – killed

Stanislovas Orlavičius (b.1956) – 35 yrs old – killed

Ričardas Rabavičius (b.1970) – 21 yrs old – injured

Tomas Šernas (b.1962) – 30 yrs old – injured

In the video images on the screen, I recognized the desk and the teacups, and thought, Oh my God. I was just there last month, drinking from those very teacups.

* * *

Almost two months earlier, on June 3rd, the InfoBureau received a call from the Medininkai customs post near the Belorussian border that seven APCs (Armored Personnel Carriers) arrived and parked nearby. The strange thing about this it was the middle of the day – all the other attacks occurred in the middle of the night. I volunteered to ride out to the post with Arvydas to check it out, since I was the only one with gas in my vehicle. Gorbachev’s ongoing economic blockade continued to impact the economy. It wasn’t unusual for me to ride out to verify report of Soviet military activity.

Arvydas grabbed the video camera and we were off on my Jawa 350 with a sidecar. My motorcycle was experiencing a multitude of mechanical issues due to the lack of parts and proper maintenance and questionable fuel. The furious 20 mile ride to Medininkai stressed the engine so much, that just when we arrived, the bike died. We coasted past the Soviet APCs and soldiers, who stood up to get a better look and gawk at the strange sight of a woman riding a motorcycle. We smiled and saluted the soldiers to add to their confusion, jumped off the bike, and pushed it to the customs post.

This post was attacked before. I remembered taking the call on May 24th. The Soviet military attacked four other customs posts that same night. But even that wasn’t the first time. The Medininkai post was attacked in January after the Soviet military attacked civilians at the TV Tower. A Lithuanian worker was beaten by Soviet forces and hospitalized with cerebral hemorrhage. The old Medininkai post which Soviet soldiers destroyed and burned down in January still stood behind the new post.

Soviet soldiers destroyed and burned down the Medininkai post before the July 31 deadly attack.

Arvydas headed toward the APCs to discreetly film the soldiers through a gym bag and ask them questions.

Two customs post workers stepped out of the post and asked, “What’s wrong? Do you need help?”

“I don’t what’s wrong,” I said.

“My grandpa has an old bike. I’m constantly fixing it. Let me take a look,” the guard said.

While he began immediately fixing my bike, the other guard took me inside the post and offered coffee. Even though there were Soviet APCs and soldiers parked outside, he went about preparing a cup of instant coffee as if this was a typical occurrence.

The truth was, after living so many months under martial law, and with the ongoing Soviet military threats and aggression, even I, a privileged American was getting used to the uncertain times living in the middle of a revolution. Other workers joined us and were amused to meet an American girl with a motorcycle. While we drank coffee from teacups, we joked around and flirted a little.

We returned outside to check the progress on the bike. Arvydas had returned and was helping .

“Did you learn anything from the soldiers?” I asked.

“They said they were waiting for gas,” he said.

“I don’t trust them,” I said.

“None of us do,” the guard said, turning back to the bike. “Say, why is an American girl like you here in Lithuania?”

I described how I came to Lithuania in January and was living in Vilnius and working at the InfoBureau office.

He perked up, “Do you work with Rita Dapkute? Are you one of the people who takes our calls when we report Soviet military activity?”

“Yep, I’m one of those people.”

“Ah, it’s good to put a face to the voice, that is, when we need to call in to report when the Soviets show up.”

“Hopefully you won’t have to call,” I said seriously, “I mean, you’re here all alone at night without weapons, no way to defend yourselves, and with all of the attacks. Aren’t you guys scared?”

“Yes. A little,” he said, “But I know the Soviets are just going to rough us up a little to prove their point. I’ll be ok.”

“You guys are super brave.”

“Not brave, just doing our part.”

* * *

Lying dead in pools of blood shouldn’t be anyone’s ‘part,’ I thought while watching the crime scene video.

After our press releases went out to the world, the phones of the InfoBureau were ringing off the hook and I did my best to explain what occurred to foreign journalists, who were equally horrified as we were.

Later that morning Arvydas placed a newspaper on my desk. Pictures of the victims of Medininkai dominated the page.

He pointed, “I think that’s the one.”

“That one what?”

“The one who helped fix your motorcycle when we were there last month.”

“Oh, Arvydai, don’t say that.”

“Look, I think that’s him.”

A tinge of familiarity flashed through my mind.

“I don’t know. I can’t be sure.”

Arvydas covered the forehead of the young man with his finger, “Remember? He was wearing a cap.”

Oh God no. It can’t be.

The day was making me more and more ill by the minute. Those soldiers with the seven APCs who were waiting for gas’ at the Medininkai post the month before were probably doing reconnaissance work investigating the area for the July 31 attack. I tried to relive that day we were at Medininkai and searched my memory for the face of the guard who fixed my bike, for the young man who made me a cup of coffee, for the young guys who flirted with me, but I couldn’t. How could I be so selfish and wrapped up with myself and not give my full attention to those who took the time to help me?

Another co-worker entered the office and informed us, “Reuter’s reported on the Bush-Gorbachev summit press conference in Moscow. Bush asked Gorbachev about what happened at Medininkai. Gorbachev supposedly didn’t know anything about it and was mad at his people for not informing him first.”

In the press conference with President Bush, Gorbachev stated there were some ‘border conflicts’ between Belarus and Lithuania, insinuating the Kremlin did not have a hand in these murders. President Bush accepted Gorbachev’s spin on the facts. Gorbachev stated that USSR KGB Chief Kryuchkov contacted Landsbergis to help Lithuanians with the investigations to find out what happened at the Medininkai post. Kryuchkov did no such thing.

That day the InfoBureau did its job effectively. The West had the facts of the Medininkai murders before Moscow could start spinning its lies, but it was the media, the press who disseminated the truth while governments attempted to appease Moscow. There weren’t any foreign news agencies based in Lithuania. The Parliament Press Office was the West’s only trustworthy source and if the office didn’t inform the world about what was happening in Lithuania during its struggle to break free from the Soviet Union, then Moscow would’ve surpassed this information too. Gorbachev’s statements would’ve remained as the record of fact.

Two days later, Ričardas Rabavičius, the seventh victim died.

The United States sent a military surgeon to help save the life of the eighth victim, Tomas Šernas, who lived and later provided the eye witness testimony of who committed the crime: Soviet OMON forces.

Funeral Procession for the victims of the Medininkai murders

Funeral Procession for the victims of the Medininkai murders

Funeral in Vilnius for the Medininkai victims

Thousands gathered at the Antakalnis Cemetery for the burial of the victims of the Medininkai murders

* * *

In the years since 1991, I pull out that old July 31, 1991 newspaper from time to time to remind myself of the faces of the victims of Medininkai. In those days when Lithuania was striving to achieve independence, many people ‘did their part.’

Today, I must do my part and not forget those who did more than just ‘their part,’ but gave their lives.

More importantly, we must remember these men were sons, fathers, brothers and friends – they are missed each day by their loved ones. The real tragedy is that these men were taken away from their families in a political game. Their lives were maliciously cut short by the rulers in Moscow, who’ve had no regard for human life.

For many centuries, the Kremlin has waged war on the Lithuanian people. How many thousands have been killed in Moscow’s never-ending attempts to erase the existence of the nation?

The Lithuanian government has also attempted to prosecute those responsible for the tragic events of January 13, 1991. In this modern age of the internet where video and photographs allow the world to see the crimes for themselves, Moscow can’t deny the Red Army committed these crimes, although, they certainly try. However, the Kremlin has more weapons in their arsenal, and in 2018, the Investigative Committee of Russia is attempting to criminally charge the Lithuanian judges investigating Moscow’s crimes against Lithuanians in 1991.

The main perpetrator, former USSR President Mikhail Gorbachev, continues to deny any responsibility whatsoever to any bloodshed in Lithuania, despite the fact he discussed the plans for a crackdown immediately after Lithuania re-established independence on March 11, 1990. The Soviet military began seizing buildings in early January of 1991 and Gorbachev gave the Lithuanian Parliament an ultimatum on January 10th to rescind the independence act and to restore Soviet rule, or else he’ll take matters into his own hands and impose direct presidential rule. Gorbachev claimed he had nothing to do with the attack at the Vilnius TV Tower on January 13, 1991.

If that was true, why didn’t Gorbachev order the Soviet military occupying the tower for eight months to withdraw? Instead, Gorbachev blamed Landsbergis and those who desired freedom, claiming they were extremists who brought this all onto the entire country.

In the following months, the Soviet military seized another twenty-nine buildings, which Gorbachev did nothing to prevent. Since May of 1991, attacks on the border posts occurred almost daily, which Gorbachev permitted. Gorbachev claimed he knew nothing about the executions at Medininkai. Someone from the top of the chain of command gave the order to kill. I guess Gorbachev was just doing his part too, following the Kremlin’s tradition of denying Lithuanian independence – at the expense of Lithuanian lives. Even on September 6, 1991, when Moscow was forced to accept Lithuanian independence and finally officially recognized it, the Kremlin still denied Lithuania had been brutally illegally annexed by the Soviet Union in 1940 – and continues to deny it to this very day.

Today, I continue to do my part, to share my eye-witness accounts of what happened in 1991, because Moscow will continue to do their part, to lie about what happened and rewrite Lithuania’s history.

We all have a part in this world.

Do you have a part in this ongoing history?

“On July 31, 1991, here at the Medininkai customs post, Lithuanian officers were maliciously attacked and murdered”

The Medininkai Customs Post has been preserved as it was the night eight post workers were shot execution-style by the Soviet OMON.

The graves of the victims of the January 13, 1991 Soviet attack at the TV Tower and of the Medininkai murders by Soviet OMON forces on July 31, 1991