Press

Past Press

LA Times

After the failed Moscow Coup in August 1991, the following syndicated article, featuring Daiva Venckus, appeared on August 25, 1991. A One-Way Ticket To The Revolution references conversations with the journalist as expressed in the article.

http://articles.latimes.com/1991-08-25/opinion/op-1933_1_lithuanian-parliament

August 25, 1991|Sherry Ricchiardi | Sherry Ricchiardi, formerly a reporter with the Des Moines Register, teaches journalism at Indiana University. She is co-author of “Women on Deadline” (Iowa State University Press)

WASHINGTON — The overseas operator offered little hope of getting through to Lithuania last Monday, due to “problems in the Soviet Union.”

The “problems” included a coup and the ouster of Mikhail S. Gorbachev just 12 hours before. I urged her to keep trying.

Moments later, I heard the voice of Daiva Venckus, 25, a Los Angeles native who, along with dozens of others, was barricaded in the Lithuanian Parliament building in the capital city.

“They are occupying the communication centers. We are being cut off from the West,” said Venckus, who arrived in Vilnius on Jan. 15, just two days after Soviet tanks rumbled into town, leaving 14 dead.

It was 8:30 p.m., Lithuanian time, day one of the coup. Venckus, an editor for the government Bureau of Information, was struggling against the odds to get news out.

Worried that we could be cut off, she poured out accounts of tank columns on the move, assaults on radio and TV towers, thousands of protesters in the streets. She feared that the Parliament building, a symbol of Lithuanian independence, was high on the Red Army’s hit list.

“We don’t know whether they’ll try to kill us or force us out. If tanks come, I won’t leave. I’ll stay on the telephone as long as I can to tell the world what is happening,” Venckus said over the crackling phone lines. Flashes of this fierce defiance had surfaced three weeks earlier when I met Venckus for an interview while I was traveling in the Baltic. She was in Lithuania to “join the struggle for independence. I believe I can make a difference here,” she said.

She greeted me and another journalist at the entrance of the Parliament under the watchful eyes of security guards. She was pleased to find American journalists interested in the Baltics.

“Some are afraid to come here,” she said, as she guided us through the maze of electrical wires, armed militia and blurry-eyed workers who, like herself, were putting in 12-hour days. Her attire–black blazer, blue jeans and silver-tipped motorcycle boots–would have been at home in a disco.

Venckus put her career on hold to stand up for her parents’ homeland, earning 431 rubles (an equivalent of $15) per month. In July, she became a citizen of Lithuania as well as of the United States. “I am making up for what was taken away from my parents nearly 50 years ago,” she explained.

As we departed, Venckus said, “If you need more information, call.”

Now she was a voice on the telephone thousands of miles away, holed up behind cement barricades with tanks heading in her direction. There were at least two other Americans who vowed to stay.

By midnight, a crowd of 5,000 had gathered to serve as a shield in front of the Parliament. Simultaneously, Americans watched as civilians gathered around the Russian Parliament building in Moscow. Later, armed with flags, slogans and lofty ideals, they would stand off the tanks.

What drives human beings to fight guns with words? Venckus dreams of writing a book and going to graduate school. Instead, she is sitting on a powder keg. Many activists draw strength from knowing they are right. The repression of human beings cannot triumph, no matter what the price. Or maybe the courage to face tanks comes when there is nothing left to lose.

Ricardas Rimkus, a Vilnius schoolteacher who was blacklisted for voicing the wrong political views, told me that it’s easier to stand up against the enemy when “you have been stripped of everything.”

“The Communists and the KGB have made a hell for us here,” he said.

In July, I interviewed journalists who had been forced out of their jobs by thugs who occupied communication centers throughout Vilnius. Two hundred are participating in a hunger strike. “We will continue this protest until we are allowed to operate a free press,” said Skirmantas Valiulis, general director of Lithuanian television.

Valiulis knows he is high on the KGB hit list if the independence movement fails. The building where he once worked wears the scars of bullets fired the night of the takeover.

As for Venckus, she had been taking a break in the resort city of Niva, 180 miles from the capital city, when she learned of the coup this past week. “I ran to a phone to call Vilnius, but I couldn’t get through,” she recalled. She hailed the nearest cab and peeled off $61, all the American money she had, for a frantic drive through the countryside.

Back home in Los Angeles, her parents, Elena and Roma Venckus, scanned newspapers and television for news. “We notified the American Embassy that Daiva is in Vilnius,” Elena Venckus said. “We left Lithuania so that we could be free. We don’t want our daughter to die there.”

Last Wednesday, day three of the coup, Daiva was on the telephone describing how a column of tanks approached the Parliament building. “We shut off all the lights and closed the curtains. Everybody had their gas masks ready,” she said. But this time, it was psychological warfare. The tanks left without firing a shot.

Later that day, the world witnessed the triumph of the human spirit over tanks and guns in Moscow. But in Vilnius, the price still was being paid. Soviet troops advanced on the Lithuanian Parliament building. Gunfire left two wounded and a Lithuanian security guard dead. The TV reporter labeled it a “minor incident.”

Mikhail Gorbachev’s homecoming overshadowed the event.

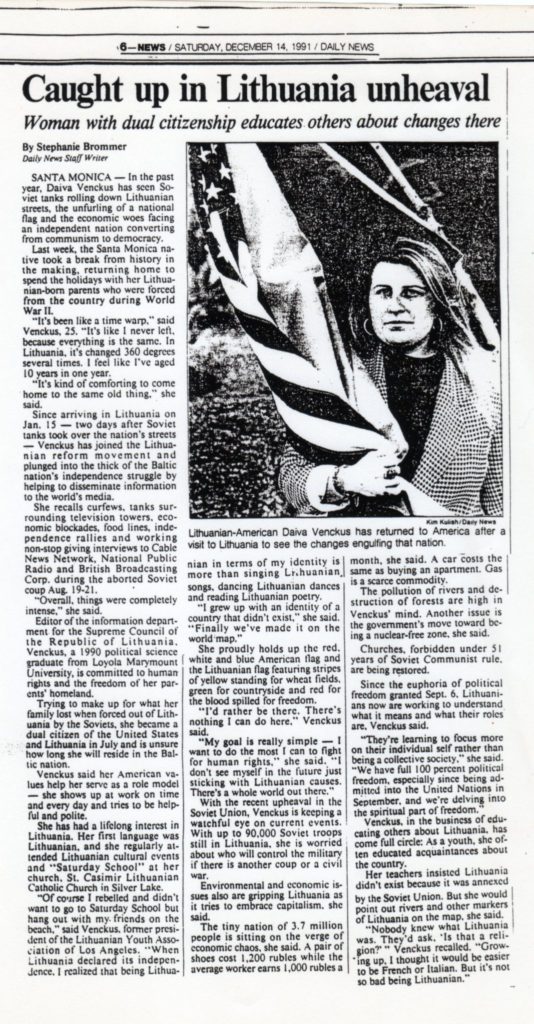

Daily News

When Daiva returned to America for Christmas visit in December 1991, she was interviewed by the Los Angeles The Daily News. (www.dailynews.com)