Chapter Excerpt

Chapter Excerpt

Inside the Barricades: Vilnius, Lithuania – August 19, 1991

Dead faces flashed through my memory when I scanned the horizon and saw the 100-story TV Tower breaking the skyline. I glanced at the deserted highway behind me.

Reality hit while I thought, I know tanks are on the way.

I checked my heart with my hand. A faint knocking met my fingertips. I should’ve been more afraid, but after living in revolutionary Lithuania the previous eight months, I’d developed the involuntary knack of shutting down my emotions to remain functional.

I handed the cab driver all the money I had—$61 US dollars and 300 rubles.

“No, it’s too much,” the driver mumbled in Lithuanian. Smoke hovered over the cigarette dangling between his lips.

“That was our deal,” I said. I shoved the money—which was worth six months’ salary—back at him.

He pushed the cash toward me. “I changed my mind. I can’t take advantage…”

“I would’ve been stranded on the other side of the country if you didn’t stop for me. With Gorbachev missing, and a coup in Moscow and tanks everywhere, this dangerous situation…”

“All right,” he said slipping the cash in his shirt pocket before placing his heavy hand over mine. “May God be with you.”

I hopped out of the taxi. A deep breath drew the summer humidity into my lungs, causing me to choke. For a moment, the world went dark.

Is this really happening?

I glanced at my watch, an official Soviet army tank commander’s timepiece I bought for $10 USD from a local gypsy. An image of a tank centered on its face. 3:45.

Heaving my tattered backpack over my shoulder, I moved along the barricades to the stairs leading to the backside of the Lithuanian Parliament building, my destination. The graffiti on a concrete block stopped me for a moment. A tank with a red circle and a line drawn over it caused me to smile.

Typical Lithuanian thing to do, plastering ‘No Tank’ symbols all over the barricades.

I looked back at my watch.

I guess I’m a typical Lithuanian after all.

Giant blocks of concrete, as if dropped from the sky like matchsticks, towered over me blocking the stairs. The rough surface bit into my palms as I dragged myself over the first block, my long blond hair in my face creating the only challenge. The barrier wasn’t going to stop an advancing enemy.

At the summit, I scanned the grassy field the size of a city block separating me from the Parliament building. I was about to run across when I saw shiny objects glistening from the grass. I froze.

What the hell?

Thin, foot-tall metal rods rose from the overgrown grass. A red plastic flag with the letter “M” stenciled and shaped like an inverted triangle hung from the top of each.

Mines? Seriously? I don’t have time for this.

The minefield tags were spaced 10-12 feet apart.

This is ridiculous.

I should’ve been scared but after living this Soviet life for the past eight months nothing surprised me anymore. This setback annoyed me more than anything else. My impulsive inner Aries took charge, driving me forward.

At least I got one up on Dad. Next time he complains about his childhood hardships of walking two miles through Boston’s snow past Irish gangs to get to school every day, I’m going to remind him of how I had to tiptoe through a minefield to get to my job.

One more barrier blocked my path to the Parliament building: a deep anti-tank ditch at the edge of the field. A ten-foot wall of dirt blocked the view. I concentrated on my feet, as the leather soles of my cowboy boots slipped in the mud along the narrow path of the trench.

“Hey, you!” a kid shouted.

Two teenagers dressed in militia uniforms with vintage hunting rifles rushed me, stopping at the edge of the minefield.

“Do you see where you’re walking? No one’s to be within 100 feet of the building!”

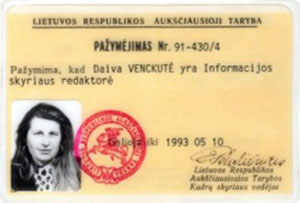

“I’m trying to get to work—the InfoBureau.” I replied, when I approached them and dug my Lithuanian Parliament ID card from my pocket.

“What’ve you heard?” I asked. “Where are the tanks?”

The young man, glimpsed at my ID, “They’re headed our way! What’re you waiting for? Hurry up and get inside!”

Lithuanian Parliament ID

The building’s perimeter was wrapped with haphazard barricades of metal and iron fencing, barbed wire, and construction materials. The front entrance was sealed off with 20-foot-tall construction blocks and adorned with flags and placards demanding freedom. Someone stenciled in large letters, “WE WILL DIE SO THAT WE MAY LIVE,” on a corner of a block which was hard to ignore. Sprinting toward the side entrance, I noticed a couple thousand people lingering beyond the barricades.

Human shields. They know what happened at the TV Tower.

After composing myself with a deep breath I opened the glass door and was processed by security. Uniformed guards filled the corridors. I dashed through the sandbag-lined hallway into the foyer of the main building. Dozens of antiquated dual-chamber hunting rifles lined the walls. Stacks of metal rods and wooden sticks the size of baseball bats were leaned in corners.

I knew the elevator would be shut down and the main stairs leading to the offices blockaded. This wasn’t the first time a Soviet attack was looming—but this time was different. It was not a surprise offensive. A column of tanks were headed our way and we knew what they were capable of. I was aware of the security procedures after working at Parliament for several months. I entered a side stairwell, which was obstructed by another uniformed guy.

“InfoBureau,” I said, flashing my ID.

He pointed upward. “Be careful. Go slow.”

The four-story stairwell looked like a tornado had deposited its debris there: clunky desks leaning precariously against the railing, overturned chairs, nets and sandbags. Various sorts of junk had been randomly pushed down the stairs in preparation to slow an onslaught of Soviet soldiers.

I crawled cautiously through the gaps in the maze; aware one wrong move might cause an avalanche of office furniture. A box of Molotov Cocktails was shoved in a corner of a stairwell landing, gasoline vapors irritating my throat as I ascended to the fourth floor through the chaos.

In the dark hallway three armed men sprinted past me when I stepped into the InfoBureau office, greeted by a cacophony of screaming phones and languages. I knocked on the glass partition of the fax-telex room where Rimvydas and Saddmas talked on the phones in Russian. I continued into the office. Snieguole’s jaw dropped in astonishment at my arrival.

I dropped my backpack, grabbed a pad of paper and pen from my desk and dashed into the adjacent room to check in for duty with my boss, Rita Dapkus.

Rita hung up the phone. “I didn’t think you were going to make it,” she said in English, “You didn’t call in.” Her usual poker face widened to a grin.

“I couldn’t get a call through. Are the lines down? What’s up with the minefield? Is the roof set to explode if paratroopers land on it?” I asked, relieved finally to be with my co-workers.

“Minefield? No one tells me anything.” She glanced up and smiled. “Though, that might be true about the roof. I think the stairs are mined too. How the hell did you get here?”

“I took a taxi.”

“What? All the way from Nida? That’s 250 miles.” Her blue eyes turned serious as she changed the subject. “Keep the curtains closed. There’re reports there might be snipers in the buildings across the river.”

I glimpsed at the heavy, rust colored floor-to-ceiling drapery covering the window in her cramped office. I tried to keep my mind from envisioning a barrage of bullets and us lying in pools of blood.

Rita leaned on the cluttered desktop and resumed the briefing, “The Soviets are on the move occupying radio and TV transmission stations—creating a complete communications blackout. They took the Kaunas station this morning.”

I flipped to an empty page in my pad to take notes but couldn’t focus.

Rita continued, “Vilnius radio was taken at noon. The Soviets occupied the telephone exchange an hour ago. Some calls are getting through. We can’t call outside of Vilnius. If foreign journalists get through, get as much info out as you can.”

“What’s happening in Moscow?”

“Only what’s being reported. Gorbachev’s ‘sick.’ Probably killed by the neo-Stalinists. Tanks are surrounding the Russian White House. Yeltsin is barricaded in there.”

“And, us?”

“Tanks are headed toward us,” Rita explained. She shook a pack of BTs, and pushed a cigarette between her lips, running her fingers through her fair hair. I didn’t know how she could stand those questionable cheap Russian cigarettes; their smoke made me nauseous. Rita had been in Lithuania longer than any other American and lived like a local.

“Word is, they’re going to attack tonight,” she continued. “Parliament is holding a closed session. There’s nothing more they can do except support Yeltsin.”

This is it, My gut churned. All’s that left is to wait. I’d been working at the InfoBureau long enough and understood what I needed to do.

As I got up to leave Rita said, “Daiva—keep your passport in your pocket.”

I laughed in my head. This is absurd.

How’s my passport going to help? If Soviet soldiers storm the building can I pull out my blue American passport like a magic shield and deflect the oncoming attack? Will the soldiers say “Hold the bullets, boys, let the American girl get through before we start killing everyone else.”

I joined my co-workers to man the phones. Calls from citizens about troop movements poured in from throughout the country.

At 5:45 a woman’s voice hollered over the phone line, “They’re here! Call someone to help!”

“Where are you?” I asked. She didn’t need to explain who “they” were.

“The telephone exchange. In Kaunas.” If the Kaunas exchange were seized, we’d probably lose all our lines.

“How many soldiers? With weapons?”

“About fifty. Wearing greens. With automatic rifles. Citizens are outside, forming a human ring but the soldiers broke through. They’re in the hallways. Hold on.”

I heard a loud slam.

She returned to the line, “I’ve locked my door.”

Two seconds later someone banged on her door and yelled something in Russian.

“What’s going on?” I asked.

“The soldiers are outside my door, ordering me to leave. But I’m not going anywhere.”

This had not been the first time I had a defiant Lithuanian on the line, and I tried to convince her to comply, “The situation is dangerous. You need to evacuate.”

“I’m not leaving my desk. I’m going to keep doing my job.”

“Please,” I said even voiced and trying not to panic, “If shooting begins, please get out of there.” I hung up and called the Lithuanian Defense Department to inform them. “Please do something,” I begged, “There’s innocent people in there.”

“We’ll do what we can,” a somber voice said.

There’s nothing anyone can do. We’re screwed.

My breath became more and more shallow as the hours dragged on, with citizen reports of the massive military hardware headed toward us:

Twenty Soviet tanks are headed toward Vilnius from the north. They were about 80 km (50 miles), or three hours away.

Another military column of eighty tanks is moving toward Vilnius from the east. That column was 100 km (65 miles) away.

Six Soviet military transport planes lifting off from Latvia arrived at an airport north of Vilnius, bringing more soldiers to Lithuania.

As evening approached, a volunteer guard appeared and stomped through our office: “Gas masks! Do you have your gas masks? Carry your gas masks at all times.”

How do I know when to use my gas mask? Do I wait until the first shot is fired?

The endless ringing of the phones gave me no time to think about the worst. I picked up a line.

“Is Parliament still standing? All radio has been cut!”

“Yes, we’re here, we haven’t been overthrown,” I assured the caller while adjusting my gas mask bag on my shoulder.

“Are you evacuating?” asked the frantic voice.

“No, we’re not going anywhere.”

Hours and hours of similar calls and reports from Lithuanian citizens poured in as I jotted the details. During the brief moments of silence, I hid in the bathroom to compose myself and to calm my heart with prayer. My anxiety was fueled by anticipation of what the next moment might bring.

The enormity of calls resumed: radio and television transmission towers throughout Lithuania seized; soldiers breaking through human shields to seize municipal buildings; soldiers patrolling neighborhoods harassing people; bridges blocked by Soviet military; soldiers surrounding us; and all those tanks headed toward us.

I didn’t understand why I didn’t feel scared—my mind was focused and alert, as if I had consumed a gallon of coffee.

Snieguole turned to me, “Line 2, English.”

I picked it up. “Hello. InfoBureau.”

“Yes hello. Is this Daiva Venckus?”

“Yes…”

“This is Sheri Riccardi. Do you remember me?”

Sheri was a freelance journalist I’d showed around the Parliament Building a month ago. My other job function was to help journalists acquire accreditation, ensure they received the latest information and provide them with translators at press briefings.

“Yeah! Where’re you calling from?”

“The U.S. What’s happening? CNN is focused on Moscow. There are no reports on Vilnius.”

“We can’t get lines out to the West and we’ve reports that columns of tanks are headed our way right now.”

Excited and relieved to have contact with someone in the West, I rattled off the accounts of Soviet troop movements and infrastructure seizures as if it were my last connection—my last chance to tell the West what the Soviets were trying to get away with. If we were going to be attacked, I wanted the world to know.

“Are you planning to leave the building?” Sherri asked.

“No, I’ll stay on the line as long as I can to get the news out,” I replied without hesitation, “No one’s leaving.”

“Is there anything I can do for you?” My heart pounded with the clarity of our circumstances.

We might not make it.

“Yeah,” I said. “I hate to ask, but if you can—can you call my parents in L.A. and tell them—tell them I’m ok.”

Is that how I get to say good-bye? Mom and Dad must be freaking out. My family escaped Lithuania so I could be free. What am I doing?

After I gave her their number and hung up, a sudden rumbling engulfed me. I was familiar with earthquakes, I grew up in Los Angeles—and this was the start of a trembler. The phones fell silent.

Did the Soviets cut the phone lines?

I glanced at my tank commander watch. 11:00 p.m.

The shaking grew. It wasn’t an earthquake.

Snieguole and I jumped to our fourth floor office window. I drew back the heavy curtains and placed my fingertips on the thin glass violently vibrating inside the wooden frame. My other hand fell over my gas mask pouch.

On the other side of the river, rows of tanks lumbered under the street lamps between buildings toward the bridge that would bring them to the front doors of the Parliament building. A mound of concrete construction blocks and an abandoned dump truck stopped the tanks at the foot of the bridge.

Dozens of gun barrels glistened in the light rain as they jolted left and right to acquire a good shot at us.

Ooooooh shit! I don’t want to die.

A teenage volunteer ran into the office shouting, “Lights out! Get away from the window! On the floor!” He switched off the lights and disappeared.

I don’t want to die! I stood frozen. I don’t want to die!

My focus shifted from the tanks to Snieguole standing beside me.

This isn’t like the movies during the dramatic climax when everyone is about to be killed and the characters start hugging and telling each other things like “you’re the best co-worker ever” or “I couldn’t have done any of this without you!”

We stood together to face death alone within the jangling clamor of our own internal thoughts.

Time slowed down while hundreds of people ran onto the bridge, scrambling over the concrete barricade, shaking their fists. The images of the dead bodies from the past eight months that appeared in newspapers, on TV and plastered across the barricades filled my mind. More blood.

The rumble of the tank engines reverberated across the bridge, along the ground to the Parliament building, and continued through the foundation to the glass pane, which shook in its frame under my fingertips.

We’re all going to die. But I’m an American. I’m already free. Why am I here?

Earlier, Rita instructed me to keep my passport on me. I’d assumed we’d escape to Poland if the Red Army attacked. But when I heard voices in the hallways yelling, “On the floor,” clearly, no one was running away. When the floor’s shaking increased, I wondered if Moscow’s army were going to rain shells and the true reason for Rita’s suggestion revealed itself.

So my dead body could be identified.

My hand released my death grip from the gas mask. I removed my blue American passport from my back Levi’s pocket and placed it more securely in my front pocket.